Empowering through knowledge. Transforming through lived experience.

Welcome to the Education Hub.

At Victims’ Voice Durham CIC, we believe education is a catalyst for change. Our Education Hub is a dedicated space where survivors, professionals, and communities come together to learn, reflect, and grow. Rooted in trauma-informed practice and shaped by the voices of those with lived experience, this hub offers tools, insights, and creative resources to challenge harmful norms, foster empathy, and build safer systems.

The legal definition of domestic abuse

The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 provides a statutory definition of domestic abuse. Domestic abuse involves any single incident or pattern of conduct where someone’s behaviour towards another is abusive, and where the people involved are aged 16 or over and are, or have been, personally connected to each other regardless of gender or sexuality.

The abuse can involve, but is not limited to:

- physical

- sexual

- violent

- threatening

- controlling

- coercive

- economic

- psychological

- emotional

Personal connection’ means the individuals concerned:

- are due to be, are currently, or have been, married or civil partners to each other

- are, or have been, in an intimate personal relationship with each other

- are, or have been, parents (or had a parental relationship) to the same child

- are relatives (the Act gives further definitions of ‘relatives’)

Domestic Abuse Statutory Guidance, July 2022

Domestic Abuse

Domestic abuse can happen to anyone but is most commonly a gendered crime by men, experienced by women. Domestic abuse is a crime. It comes in many different forms. It is devastating lives at epidemic levels nationally and internationally.

Useful Reading

Domestic Abuse Statutory Guidance, July 2022

Nicole Jacob’s, Domestic Abuse Commissioner

Coercive Control

The foundation of domestic abuse, coercive control is an intentional pattern of behaviour used to harm or punish a victim. Often described as a more subtle form of abuse that leaves invisible scars instead of physical ones.

Useful Reading

Controlling or Coercive Behaviour Statutory Guidance Framework, April 2024

Dr Evan Stark, How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life, 2007

Dr Evan Stark, Children of Coercive Control, 2024

Dr Emma Katz, Coercive Control in Children’s and Mothers’ Lives, 2022

Post-separation Abuse

For victims, abuse does not end at separation, but continues and often escalates. Perpetrators of intimate partner abuse use direct or indirect tactics to continue to harm their ex-partners, including using and weaponising children or systems.

Useful Reading

Professor Jane Monckton-Smith OBE, Homicide Timeline

Kathryn Spearman et al, Post-separation abuse: A literature review connecting tactics to harm, 2023

Economic Abuse

Economic abuse is a form of abuse where a perpetrator has control over a victims access to economic resources, diminishes their ability to support themselves financially and makes them dependent on the perpetrator financially.

Useful Reading

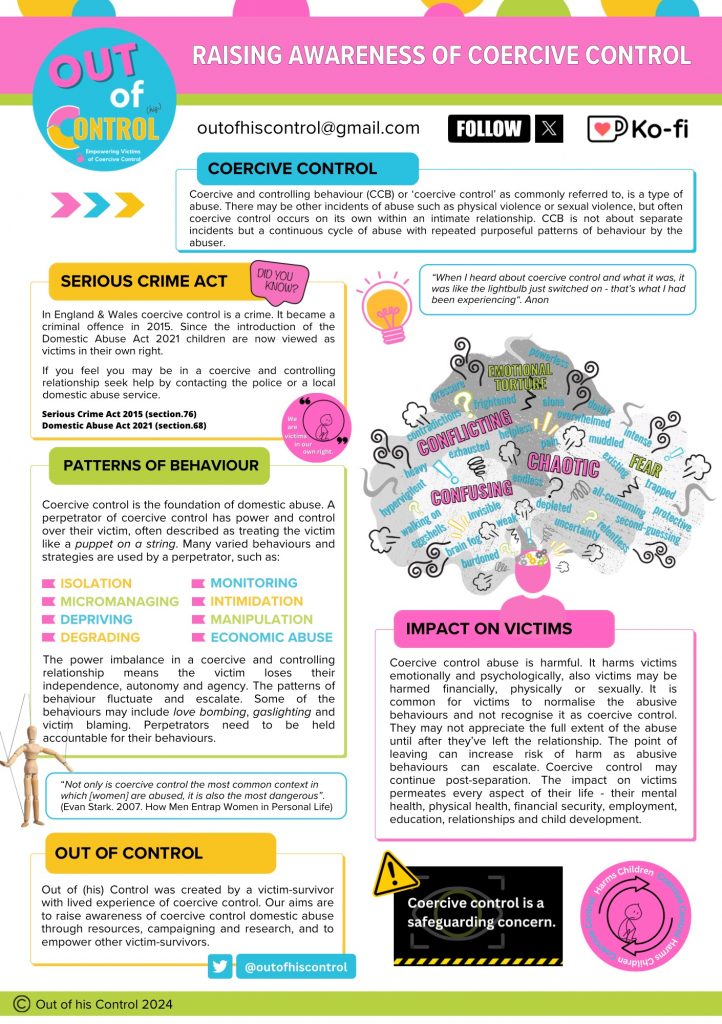

Coercive Control

Controlling and coercive behaviours – known as coercive control – are behaviours at the core of domestic abuse. Coercive control can occur alongside other types of abuse such as physical violence, sexual abuse, financial abuse, emotional or psychological abuse. Often it can occur without any physical or sexual violence being present. It can happen in any type of relationship such as an intimate-partner relationship or a parent to child relationship, or an adult-child to elderly parent relationship. Research and data tell us that a majority of cases of coercive control occur in male to female intimate relationships.

”Not only is coercive control the most common context in which [women] are abused, it is also the most dangerous”.

Evan Stark (2007) How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life, Oxford University Press.

What the law says

Controlling and coercive behaviours were first defined by the government in 2013 as:

”Any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality.

Controlling behaviour is: a range of acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance and escape and regulating their everyday behaviour.

Coercive behaviour is: an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim”.

Coercive control was first introduced into UK law as a crime in December 2015, in Section 76 of the Serious Crime Act.

It has since been added to the the Domestic Abuse Act 2021:

“Controlling or coercive behaviour can amount to an offence under section 76 of the Serious Crime Act 2025. The offence carries a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment. It is only applicable where:

- The victim and perpetrator are “personally connected” at the time the behaviour takes place;

- The behaviour has had a serious effect on the victim, meaning that it has caused the victim to fear violence will be used against them on two or more occasions, or it has had a substantial adverse effect on the victim’s usual day to day activities; and

- The behaviour takes place repeatedly or continuously”.

”It is an intentional pattern of behaviour that occurs on two or more occasions, or which takes place over time, in order for one individual to exert power, control or coercion over another”.

Controlling or Coercive Behaviour Statutory Guidance Framework, 5 April 2023

What is coercive control?

Coercive control is a continuous cycle of abuse with repeated patterns of behaviour by the perpetrator, to exert power and control over their victim.

Common behaviours can include, but are not limited to:

- Isolation

- Monitoring

- Micro-managing

- Intimidation

- Manipulation

- Deprivation

- Humiliation

- Stalking

- Harrasment

- Financial Abuse

Coercive control, like other types of domestic abuse, often continues after separation (post-separation abuse).

What the experts say

Professor Evan Stark was an American sociologist and leading expert on coercive control, developing the concept “coercive control” as a framework that shaped legislation in the UK, US and beyond, leading to the introduction of a coercive control law in 2015.

“Coercive control is not primarily about violence. It is about subjugation: stripping away autonomy, dignity, and personhood”.*

He described coercive control as being entrapped or being in a hostage like situation. His framework of coercive control explained how domestic abuse is not always about separate physical incidents.

“The victim becomes captive in an unreal world created by the abuser, entrapped in a world of confusion, contradiction and fear”.*

He was a researcher, social worker, lecturer, speaker and sociologist. His award-winning book How Men Entrap Women In Personal Lives was released in 2007, later revised in 2024. Released the same year was Children of Coercive Control.

”Not only is coercive control the most common context in which [women] are abused, it is also the most dangerous”.*

*Evan Stark (2007) How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life, Oxford University Press.

“Children and young people who have a coercively controlling parent are not just witnesses. They should be supported as co-victims and co-survivors.”*

Dr Emma Katz is a world leading expert on coercive control and domestic abuse. She is an academic researcher, author and lecturer. She is an internationally renowned expert speaker on coercive control.

”Coercive control pervades [children’s] entire world, as it does the world of their mother, profoundly altering their experience of life”.*

Her academic research focuses on the impacts of coercive control on children and how perpetrator fathers can sabotage the mother-child relationship using coercive or controlling tactics.

“Coercive control traps children and mothers together in a cage of control”.*

Dr Katz has provided training to thousands of people globally, helping to shape understanding of coercive control amongst professionals and victim-survivors. She continues to bring her research to the public online via her website or her articles on her Substack platform.

*Dr Emma Katz (2022) Coercive Control in Children’s and Mothers’ Lives, Oxford University Press.

What the other experts say, the real voices

People with lived experience of domestic abuse are the real experts. Victim-survivors live it, feel it, hear it, see it, every day of their relationship, and often for years after they leave. The voices of victim-survivors must be central to any research, response or support. Here we share some insights into the experiences of victim-survivors of coercive control.

Tanya

I knew things weren’t right but I could never put my finger on it. I felt scared of him but couldn’t explain why. I felt like I couldn’t leave but did try many times. I felt like I was always walking on eggshells around him. When I finally left with the kids I thought we would feel safer and happier. But I didn’t know it would just get worse.

Niamh

Ellie